As Sister Jane Frances Morrissey talks on the phone, her small hands are at work. For the first time in a long time, Morrissey — a Catholic nun approaching 80 years old — has picked up her knitting needles. She plans to send her crochet project to a Christian peace advocacy group, in celebration the organization’s 50th year anniversary.

Eventually, the voice over the phone asks Morrissey how many times she’s been arrested.

“Six times,” Morrissey says. “But the real honest answer is: ‘not enough.’”

Standing at 5-feet-tall, with an infectious smile and a bright white pixie cut, Morrissey’s look does not read ‘powerhouse.’ But her reputation and influence are widely known and admired in Western Massachusetts. As an activist, nonprofit founder and arrestee, the Greater Springfield area’s favorite adorable nun makes a sizable impact.

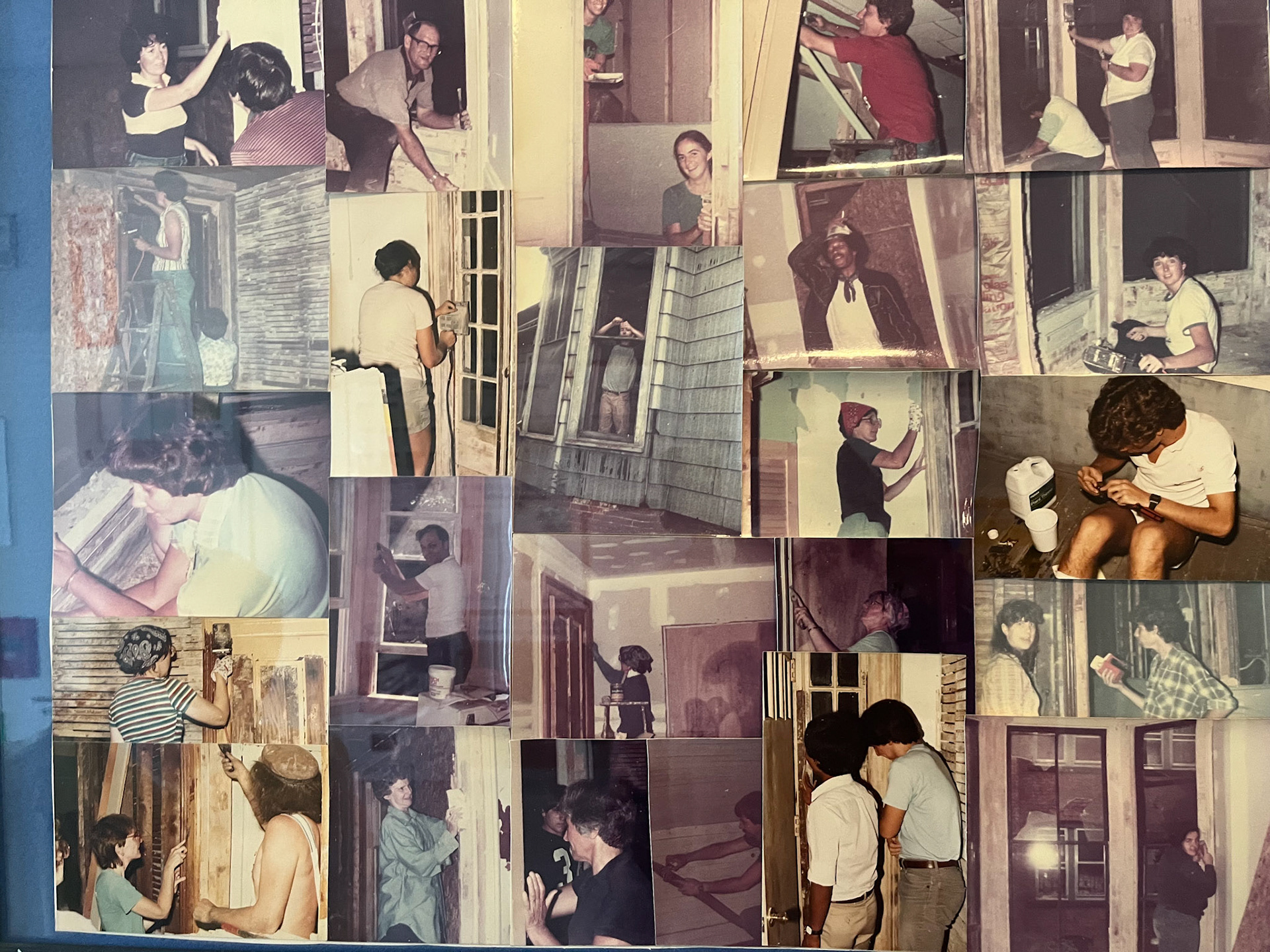

Sister Jane Morrissey points to photos from the founding of The Gray House, an educational nonprofit she co-founded in Springfield's North End.

Morrissey’s run-ins with the law are a result of her stalwart stance against war. Morrissey and other global-peace advocates practice civil disobedience by going where they are not supposed to be — for example: the front entrance of the Springfield Federal Court House — and quietly demanding an end to brutality at home and abroad. Sometimes they get arrested.

The conditions in the “lock-ups” where protestors are held are often less than comfortable. Morrissey remembers sitting on cold, concrete floors and even being locked in a broom closet when a jail ran out of cells.

Morrissey has never had to spend long periods of time in jail for her activism. But she is prepared to.

“We have to be willing to suffer on behalf of our brother and sister, who is in danger of death, wherever they may be,” Morrissey said.

Morrissey strongly disapproves of violence in all forms. She does not believe that war, in any context, can be ‘justified.’ She practices total nonviolence in her protesting. She even takes issue with some contact sports.

“I find football a very violent sport-business,” she said. “I refuse to watch it.”

People around Morrissey recognized her passion for peace before she saw it in herself. When Morrissey taught at Cathedral High School during the Vietnam War, she was one of the first teachers that student Jim Harrigan turned to for help in organizing his application for ‘conscientious objector’ status.

“I knew that she would be supportive of my sense of morality,” Harrigan said.

Once, a student approached Morrissey and said that she was “the most nonviolent person” that the student had ever met. This comment struck a chord with the nun.

“I had never heard the word ‘nonviolent’ before in my life,” Morrissey said. “How can I be what I don’t even know about? I thought, ‘Well, maybe there’s a way to find out.’”

The first time Morrissey risked arrest to protest violence was many years after that, during the US invasion of Iraq. Her roommate and fellow Sister of Saint Joesph (SSJ), Annette McDermott, remembers how upset Morrissey was by the war.

While the sisters they lived with watched the coverage of the invasion on TV, “Jane was wailing,” McDermott said. “She was just wailing.”

After that, McDermott told Morrissey, “If I felt the way you do, I would have to get arrested.”

So Morrissey took her roommate’s advice and got arrested. And then she got arrested again. And again.

“I can’t be silent,” Morrissey said. “If I don’t do what my conscience tells me to do, I won’t have peace.”

Only once has Morrissey turned down the risk of arrest. The Irish-Catholic nun had been “banned and barred” from the premises of The Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation (WHINSEC) — formerly known as the School of the Americas — in Georgia. The School of the Americas was famous for training personnel from Latin American militaries in armed combat.

Morrissey had traveled to multiple Latin American countries as part of her religious and academic studies. She lived and prayed alongside the poor in Columbia, Bolivia, Peru and Guatemala. She had seen the devastating consequences of US involvement in those countries first hand, and she wanted to take a stand.

Morrissey planned to protest against US investment in foreign wars — and risk a lengthy prison sentence — by breaching the Ban-and-Bar order. However, she decided she was needed at home, the North End of Springfield, to help her community heal after a series of violent acts there.

In the late 1990’s, 13 young people from Morrissey’s parish, Blessed Sacrament in Springfield, died by gun violence over a short period of time. She had gotten to know many of the young people and families affected by the violence personally.

“I think about [one victim] whom I knew since he was a baby, and seeing his mother carrying him,” Morrissey said, her eyes watering and her petite frame trembling, “and then coming home from a trip to Latin America to find out he’d been killed at the gas station.”

Morrissey stayed in Springfield’s North End to serve her neighborhood and parish as it mourned those losses. The city of Springfield has remained the nun’s physical and spiritual home ever since.

Sister Jane Morrissey opens gifts recognizing her contributions to the Springfield community.

Pam Robbins, one of her closest friends, says many people throughout Western Massachusetts look to Morrissey for support and guidance.

“I heard one person refer to her as a mystic,” Robbins said. “Then other people have said, ‘there are saints who walk among us.’”

Morrissey’s positive reputation comes, in part, from her community organizing. Along with other Sisters of Saint Joseph, Morrissey has co-founded 2 nonprofit organizations dedicated to helping young people and families in Western Massachusetts: The Gray House in Springfield and Homework House with three sites in Holyoke, MA.

Keeping charitable organizations running and funded for so many years is no small feat according to McDermott, who worked at Mass Mutual and is familiar with the process of how nonprofits retain finances.Morrissey is a “force to be reckoned with,” said Robbins. “But she doesn’t present that way.”

Even Morrissey’s close friends admit they underestimated her when they initially met her. At first glance, they just saw her as a ‘cute little nun’ or a ‘hippie nun in a poncho.’

But now they know better. After years of living together, McDermott often witnesses Morrissey’s ability in utilizing her social connections and powers of persuasion to help neighbors in need.

“You remember this sister that blew your mind apart. And then you're like ‘Oh wait, let me help her a little bit,’ and then you realize you're signing over your will,” McDermott said.

Maureen Broughan, the other co-founder of the Homework House and a fellow SSJ, says Morrissey sets an example of how people can use their God-given gifts for Christ-like purposes.

“She's got a brilliant mind. And yet, she never uses or abuses it. She uses it only to enrich other people.”

Broughan attributes Morrissey’s charitable instincts to Morrissey’s family and upbringing, saying generosity is “in Jane’s DNA.”

Morrissey’s younger brother, Richard Morrissey, said their parents raised the seven Morrissey children to be “truly Christian.”

Richard Morrissey remembered that his parents hired some of their close family friends — people the children called ‘aunt’ and ‘uncle,’ even though they weren’t actually related — to tutor Jane Morrissey and some of his sisters. The girls already did well in school, but Morrissey’s parents figured that the family friends “needed the extra cash.”

But even with the emphasis on Christian values in the household, Morrissey’s father was hesitant when she first showed interest in entering religious life. At 16 years old, Morrissey had decided she wanted to be a nun, but her father urged her to go to college first.

“Are you a woman?” her father asked. Morrissey knew that she was still a child. So he continued, “I want you to get all the education you can, and then you can make a decision about your life.”

So Morrissey finished high school and attended Elms College — formerly known as College of Our Lady of the Elms — in Chicopee, MA. After her senior year at the Elms, Morrissey planned on entering a contemplative community and scheduled a visit to one. But, the death of her father changed her plans.

“My dad died just before I was supposed to go there for a weekend, and I couldn’t even write to the community and explain why I couldn’t come. I just couldn’t do it.” Morrissey said. “It was like if I wrote down my dad had died, it became more real for me.”

Morrissey found out that her father shared, in some of his last words, that he believed Morrissey had truly become a woman. He also mentioned the possibility of her joining the order of the Sisters of Saint Joseph.

The SSJs had been Morrissey’s teachers throughout her early years. At that time in her life, she remembered them with “the kind of contempt that familiarity can breed.”

“I didn’t want to enter that community if it was the last community left on earth,” Morrissey remembered, embarrassed at what she calls the ‘snobbishness’ of her youth.

But after graduating college and moving to New York in order to discover herself, Morrissey realized her father had been right. The SSJ mission “to unite neighbor with neighbor and neighbor with God” was Morrissey’s calling and aligned with the values her parents had instilled in her.

A sign welcoming guests to the Springfield Gray House location in multiple languages.

As a child, Morrissey helped her mother bake cakes and cookies for neighbors they knew were in mourning. Morrissey heard that her father, a lawyer, used to provide discounted legal services to those who needed it and sent his richest clients to new, young lawyers who could use a leg up.

Morrissey frequently reflects on a time she watched her mother use the teachings of the Bible to get the children to behave. Morrissey — then in her early teens — was doing chores, while her younger siblings were play-fighting in the yard. Morrisey’s mother stepped outside.

“Jesus said,” the mother stated softly and paused. The play-fighting stopped. “Blessed are the peacemakers.”

And that was the end of the brawling.

“I remember that afternoon so clearly,” Morrissey said. “I often think that’s when I started to want to be a peacemaker.”

When Morrissey remembers the Westfield home where she was raised — or as her family calls it, Sunshine Hill — her eyes dance around the room as if the walls of the bright-yellow Victorian house are being reconstructed around her in real time.

“We always had everyone welcome in our house,” Morrissey remembers, smiling. “Everyone was like a member of the family.”

These days, Morrissey hosts a lot of her own guests at the Springfield home she shares with McDermott. Morrissey has made a habit of sitting in an Adirondack chair on the front porch, and — about a month after Morrissey moved in — people started coming up the steps to visit with her, McDermott said.

“This is great,” McDermott laughed. “She’s already adopted all these people.”

But Morrissey doesn’t refer to her neighbors — from all ages, walks of life, and corners of the world — as her children. She calls them her siblings in Christ.

To Morrissey, ‘Sister’ isn’t just a title; it’s her calling.